Today, I shared a working paper titled “AI Actionability Over Interpretability” on Substack and LinkedIn. I propose taking a pragmatic approach to risk managing and building trust in generative AI. Instead of trying to understand and interpret AI model calculations, we should structure their use so that actionable fixes can be made when things go wrong. Chain-of-Thought reasoning, Chain-of-Prompts scaffolding, and agentic tracing hold promise in this regard. Notably, these techniques are also being explored and used in medicine, another high stakes field where transparency, reliability, and the ability to fix things quickly are critical.

One of the practical challenges with AI model interpretability stems from their use by enterprises, including financial institutions. While most interpretability research focuses on either input/output token relationships or the activation parameters of an LLM’s neural network, additional components are utilized and relied upon, complicating any interpretability analysis.

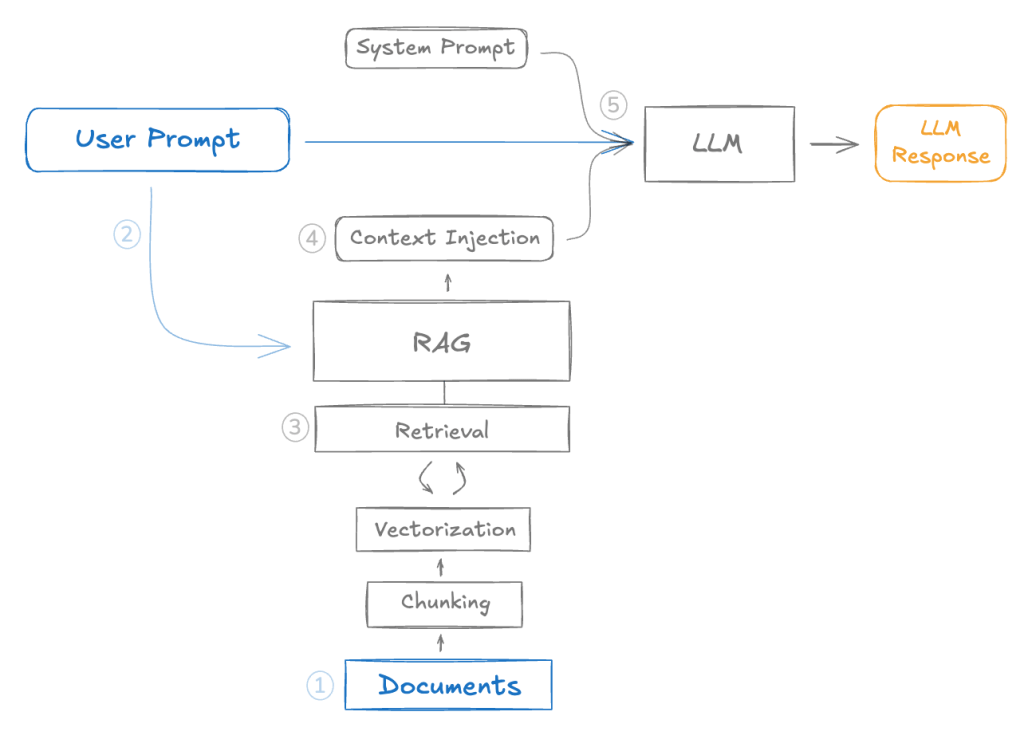

The graphic below depicting how RAG systems interact with LLMs is excerpted from the paper:

Such arrangements greatly limit the practical utility of most interpretability approaches. My paper proposes focusing instead on ensuring actionability through observability — i.e., being able to see enough to act when things go wrong. Chain-of-Thought reasoning, Chain-of-Prompts scaffolding, and agentic tracing hold promise in this regard.

This is excerpted from the paper:

Under a CoP workflow, a bank would establish a structured sequence of prompts and use the model-generated responses as the basis for the final recommendation memo to a BSA/AML compliance officer. For instance:

Prompt 1: “You are a BSA/AML investigator. You must follow 31 CFR 1020.320, FinCen SAR narrative guidance, [bank policies …], and … Cite rule numbers and policies when making evaluations and recommendations… ”

Prompt 2: [Upload transaction information] “Summarize the transaction and identify all elements using the proper format consistent with bank policy […]. Double check to make sure the formatting is correct.”

Prompt 3: “Use this red flax matrix [link] and label each flag TRUE/FALSE. Double check the sanctions list [link] and adverse media.“

Prompt 4: “Generate a risk probability score (0-100). List top 5 drivers with weight percentages. Explainable format only.”

Prompt 5: “Given [transaction_id] fetch linked entities [customer_id, device_id…] and summarize unusual patterns.”

Prompt 6: “Propose <[5] possible explanations (legit or illicit) ranked by likelihood; cite which flags support”

Prompt 7: “List any missing KYC/EDD elements that materially affect the decision”

Prompt 8: “Write a 1-2 page narrative in third person covering who, what, where, when, why, how, in chronological order in under [5,000] words. For cases with [risk score of ….] provide counterfactual analysis in under [2,000] words.”

Prompt 9: “Validate that the narrative includes all essential SAR elements, references UTC dates, omits PII. Return PASS or list fixes.”

Prompt 10: “Based on the risk score, flags, narrative, and bank policy thresholds, provide a recommendation of File SAR, No SAR, or Escalate, plus rationale with clear mapping to supporting data, analysis, and CFR citations…”

Under this CoP approach, both the number and precise wording of each prompt would be predefined and managed by the bank’s compliance department, rather than being generated dynamically by the AI model though CoT reasoning. This deliberate prompt design embeds transparency, comprehensiveness, and consistency into the process and serves as external scaffolding for the LLM’s reasoning toward the final recommendation. In the event of an adverse outcome – such as a false positive or a false negative recommendation – the structured chain of prompts allows reviewers to pinpoint the step or steps that produced the error and to amend the relevant prompt or address the underlying issue as warranted.[1]

[1] In the medical field, “chain of diagnosis” (CoD) frameworks have emerged, whereby LLMs used for diagnosing patients utilize multi-step reasoning chains that emulate how physicians might approach a case. See Junying Chen et al., “CoD, Towards an Interpretable Medical Agent using Chain of Diagnosis,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2407.13301 (2024). From that perspective, the AML example presented in the text approximates a “chain of investigation” framework. In theory, distinct frameworks for different tasks could be developed.

Leave a comment